This week, the Government is hosting a grand event aimed at trying to interest big foreign capital players in financing capital works in New Zealand, particularly its big rural motorway programme.

Financing vs funding: a quick explainer

The key word in the sentence above is financing. It is important to be clear what this means. We will still all pay for these projects; we, New Zealanders, will remain the funders.

Financing, whether via a private-public partnership (PPP) or some other scheme, is the act of borrowing money to build something. Funding is actually paying for that something.

If that something is financed, then funding it will mean paying for interest, and risk, and other costs as well as repaying the loan principle, for the construction of the thing itself.

PPPs are typically very long-term deals, and are characterised by considerable complexity, including not just building but also operating the asset for the duration of the deal. Typically, in simple cash terms this means paying several times the plain sticker price of the construction of the project itself.

So why finance? Among the attractions of financing for the funder (say, the current government) is that they get to essentially spend future governments' budgets now – by committing those governments (and those future people) to ongoing repayments, often over 20 to 30-year periods.

Other advantages are easier to achieve if the project in question generates some form of income, as this can contribute to the repayment. In transport, examples include public transport fares or road tolls.

The two current highway PPPs in NZ are what's called "availability PPPs", as they have no income except payments from NZTA. The provider's performance is evaluated on various metrics, including the maintenance and safety record over the life of the PPP. In other words, they must keep the project available to be used, under very strict criteria (although this aspect has now broken down for Transmission Gully).

The art of the deal

Here's the government's official PPP framework, by Te Waihanga/ the NZ Infrastructure Commission.

The coalition government is currently seeking foreign partners to finance its infrastructure programme, which these big financiers may do if it looks lucrative enough for them.

As the headline below says, the government is promising 'A big opportunity'. They're hoping these big finance fish see an opportunity to make money, and that the resultant deal is also an opportunity for the country. As with any deal, it's fair to ask, opportunity for whom?

Is it worth it?

To start with a general observation, this idea – of borrowing against the future to deliver projects – can work for New Zealand, but only if these two questions are answered:

Does the project truly add value to the nation? In other words, projects must be guaranteed to make us richer, happier, and safer; more able to weather the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune (apologies to the bard). And moreover...

Is the project not just value-positive, but so valuable that it remains so, even once you add in the additional costs of the financing and risk premiums?

Beyond these general tests, there are further questions specific to this moment:

What's the risk?

International capital is only interested in three things, and they want these three things all together, or no dice. They want:

big, long run projects (i.e. high )

that deliver above long-term average returns (i.e. high return),

with sovereign (government-level) guarantees over the full lifetime of the contracts, including exchange rate risk.

So, coming back to this week's event: how can the government attract lots of bids to make this event a success? By offering high government-guaranteed returns and assuring a stable political and economic environment.

Political Risk

Might a future government just cancel big deals with international companies? Surely New Zealand governments don't do that? Except ferries, right?

So how convincingly can this coalition government persuade investors that that won't happen again?

Labour has been invited along to the event, presumably to try to get them to promise they'll never reconsider any deal, no matter how they view it. Is this likely, or likely to be credible?

Regardless, if investors view us as a less reliable counterparty, they will want added risk premiums and harsher penalty clauses.

Economic Risk

Basically there remains the one big issue at the absolute heart of this: truly, how valuable are the proposed projects?

Does more tarmac, automatically, anywhere and at any cost, make us richer as a nation and thus more able to pay off these projects? Do they pay for themselves? How certain is that? Will our future selves and following generations thank us for committing them to these debts?

Whose opportunity?

Financing projects does enable them to be built earlier than otherwise, so the benefits are experienced sooner – but at a higher overall cost. And that reduces net project value. So projects must be really valuable for this approach to be appropriate.

All the other benefits that are often touted in favour of these financing schemes – innovation, etc – should be considered as marketing, and not real, because they can also be accessed through more traditional procurement processes (e.g. alliances).

Unless of course we miraculously receive really low cost, high-quality bids that are fully credible and locked-in, and that endure for the entire lifetime of the deal. Recent experience is not encouraging here.

And this brings us to...

Technical risk

Technical risks increase with the better-looking offers. Even if we can persuade ourselves of the certain value of the projects, we have to ask: how fixed are the costs?

Will we, as we did with Transmission Gully, find ourselves paying out more than the contracted sums, just to keep the project going to compleition? Or, again as with Transmission Gully, will we end up in expensive litigation with these big foreign players?

Who are the cleverer negotiators: our public servants, or these big international players? Who will control the documents that will govern every detail of these projects for multiple decades?

The issue of project value should not be downplayed in the rush to attract money and get construction underway.

Precedent

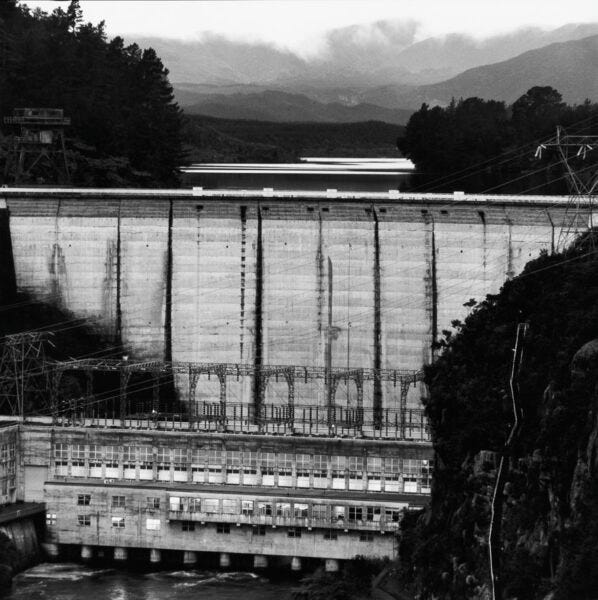

Last century's massive undertaking to generate and distribute electricity to the entire nation, enabled a clear step up in prosperity and wellbeing. Truly transformational. Those dams we still so rely on!

I would also argue that the broadband programme of the Key era was another infrastructure investment that significantly changed economic possibilities. It really came into its own when the pandemic suddenly arrived and disrupted everything, supercharging the value of online connectivity, and adding resilience to the economy and society.

So we have to ask: are the next projects in the RoNS pipeline as transformational as Think Big and widescale broadband? For me, it's very difficult to see this extremely expensive programme as achieving transformation. At best, it offers incremental improvement. Getting people and goods somewhat quicker to market is indeed somewhat better – but it is not a revolution.

Think of the opportunity cost of signing up to billions and billions of future foreign debt for parallel rural motorways, especially where the current route is nowhere near capacity. These routes may have other issues that need addressing, but no goods are currently failing to reach market.

It is very hard to see a huge step-change here, required to justify the big bet. Indeed, in many cases the existing route could be upgraded, or have additional segments added, at much lower scale and cost. This would free up capital, and debt capacity, to be deployed on other truly ambitious, transformational programmes.

Resilience

Better, safer, more resilient roads are always welcome. But it remains hard to see these new roads generating sufficient new wealth to cover their eye-watering costs, now made greater through financing.

And anyway, how should we think about resilience in this new and unpredictable age?

Physical resilience is one thing; the ability for critical infrastructure to survive earthquakes or the ever-increasing risks of weather events. But risks to global supply chains and the trading economy in general are also clearly now higher than ever, and we have recent experience of hits to both. It is hard to see how betting the farm on more rural highways rugged-ises the economy against shocks to the international supply-chain, and economic/war/mad king risks.

Think big, and different

Instead, imagine a programme of capital-intensive works that significantly reduces our dependence on imported fossil fuels. A huge build-out of renewal generation, incentive schemes for distributed generation. Electrify every farm and factory. Electrify and mode-shift transport. Reducing the $6-9 billion annual cost of oil – a fortune in foreign exchange we are forced to make every year. Building real self-reliance in energy and movement. As well as, critically, freeing up actual money to fund this financing opportunity.

Now that is a truly transformative opportunity.

I am aware this was the thinking behind the (often disparaged) Think Big programme of the 1970-80s National government, the attempt to build energy independence. What's different is the technology now actually exists to make this possible, and is also the lowest-cost energy source available.

I also note this is the kind of thinking behind the generally successful Inflation Reduction Act of the previous US government, with the economic benefit known as home-shoring.

Furthermore, in alignment with current policy objectives, it is relevant to note that renewables are structurally deflationary: once built, they deliver value without requiring constant inputs. Combustion, the endless burning of things, is structurally inflationary. Combustion-based economies require constant feeding with inputs.

There are other co-benefits too of course.

Resilience is not just about storm events.

Think Big was an interventionist state economic strategy of the Third National Government of New Zealand, promoted by the Prime Minister Robert Muldoon (1975–1984) and his National government in the early 1980s. The Think Big schemes saw the government borrow heavily overseas, running up a large external deficit, and using the funds for large-scale industrial projects. Petrochemical and energy related projects figured prominently, designed to utilise New Zealand's abundant natural gas to produce ammonia, ureafertiliser, methanol and petrol.

So, although it is largely taken as a given now that Think Big was a disaster, perhaps it was just 40 years too early? Especially as it tried to replace one fossil fuel with another in many cases. Whereas now it is obvious that it is combustion itself that needs replacing, and that the technologies to do so are now available, and will make us richer and freer, the faster we do so.

Anyway, we should be honest and see that what is being proposed here by the current government is just as risky, in that it is really the same as that earlier programme: locking us into overseas borrowing in the hope that the benefits will outweigh the costs. It is Think Big redux, but just for roads. So, Think Big without ambition for structural change. Think small in ambition, while still big in debt.

I would rather the government – any government – did think big, and more carefully, when signing us up to major forex debt. I want them to make sure that if we borrow large against the future, it's only for things that will make us richer, freer and more resilient in an increasingly mad world.

This is the real Big Opportunity.

But nothing like it appears to be currently on the table.

PS For those interested in Think Big, its conflicted reputation, and its legacy today, check out this fascinating 2020 profile of Bill Birch (Muldoon's Steven Joyce) from the Otago Daily Times. There's great detail:

Think big was not a failure. Its costs were being massively reduced by real interest rates, setting us up nicely. But then the lying looting priests of deceit privatised them before we could profit as a nation.

Go figure, marsden point; sold to oil and gas in the name of ‘market efficiency” 🤣.

Pure cartel politics

Excellent easy to read article on a major current topic. Thank you Patrick Reynolds!

Mark Thomas