Patrick Reynolds is deputy chair of the City Centre Advisory Panel, and a previous director of Waka Kotahi/NZTA.

Recently there has been some good attention on New Zealand's relatively low productivity. Just last week the Mayor led on this issue:

Brown stressed that Auckland’s economic future relies on shifting from low productivity and long hours to high-value, scalable innovation.

“New Zealand is one of the least productive OECD countries. We work longer, but produce less,” he said. “We need to lift real GDP per capita—and Auckland must lead that charge.”

In his speech the Mayor focussed on attracting and supporting high productivity sectors to set up in NZ and particularly Auckland, and this is a very important issue that needs attention. But here I want to focus on an additional key issue that effects the productivity of all businesses, high tech or otherwise, new or existing...

The role of urban form and transport infrastructure decisions in productivity

So what is productivity? It is essentially a measure of efficiency, how well we're doing. Sounds dry, but it really really matters, it is all about how prosperous, or otherwise, we are becoming; whether our daily efforts are actually helping improve or reduce our ability to maintain a good quality of life. This is not about the distribution of wealth, but about how much there is in total. Whatever our aims for society this measure is always critical - it's the size of the pizza, but not how it is cut up and shared out.

"Productivity isn't everything, but in the long run, it's almost everything" -Paul Krugman

Whatever it is you want - grand public institutions, high quality infrastructure, a broader tax base, wider redistribution (eg universal basic income), a stronger military, more teachers and doctors, whatever – a more productive economy makes it more possible and the tradeoffs to achieve them less savage.

Building the original Chief Post Office downtown, converting it to a train station (Britomart, now Waitematā), then through-routing those trains (via CRL), has required public wealth over different generations. Building these things at all, let alone to a high standard, requires surplus, spare wealth beyond subsistence.

We can and should argue over how best to spend any surplus, but those arguments get a lot easier when it is increasing, so a good starting point is to include things that deliver greater positive returns, i.e. enable higher productivity.

Productivity is spatial

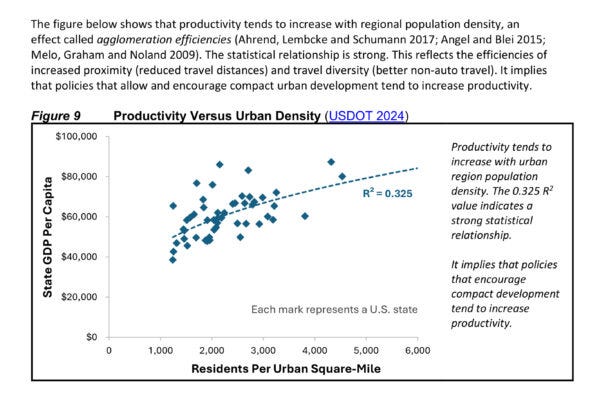

Productivity is technological, but it is also spatial. Cities everywhere essentially exist because their concentration means they are more productive. New Zealand is no exception to this: here's a recent slide from a study commissioned by the City Centre Advisory Panel:

This is a quick way of illustrating just how productive the Auckland city centre is, at just 4.3 square km. (Note: it's frustrating that the colours aren't consistent between both pies; and sorry to Matt to be putting pie charts on a GA post!).

This tiny area generates nearly as much GDP as the mighty Waikato (below).

Because cities are engines of productivity, it is important to get them right. To increase productivity we should increase the city-ness of our cities, as these are the petri-dishes in which efficiency flourishes. This is why the recent timid planning changes in response to PC78 are so disappointing. Reducing the size of our already tiny city centre to an even smaller subset will not help this problem, as very well covered by Tim Welch in Newsroom.

Productivity and transport investment

A key way to optimise this spatial efficiency is to invest in the kinds of transport infrastructure that enable and enhance it. Which is why the CRL and other more spatially efficient transport systems are so critical to Auckland.

But that's not all: a fascinating new study from The Victoria Transport Policy Institute has just dropped, and it offers some really critical insight. This suggests some of our official assumptions about what works for increasing economic efficiency via transport investment might now be actually be making things worse. How so?

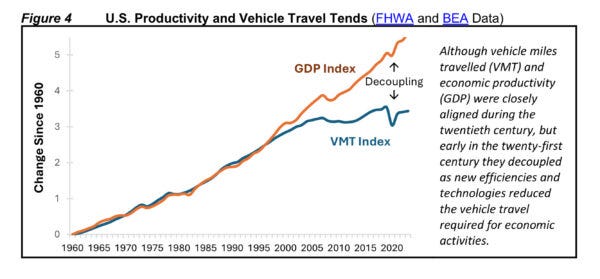

For pretty much all of the 20th century, GDP growth was largely in lockstep with both oil consumption and the quantity of driving being done. This makes sense, as oil-burning motor vehicles enable much more in the way of movement than the horse and cart. This not only led to more travel of more people and goods more efficiently; it also enabled whole new spatial patterns at greater distances, as these new machines more efficiently addressed the physical barriers of both distance and gravity.

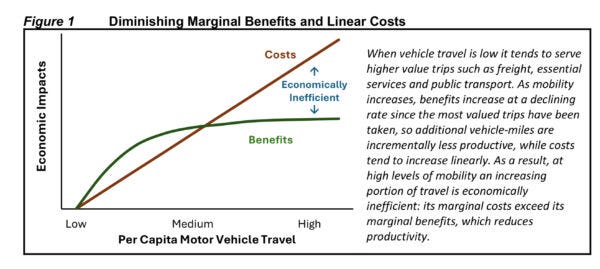

But it also makes sense that this boon has its limits. Vehicles not only overcome longer distances, but, in large numbers, they require more space, forcing an ever greater spreading out. On top of this, they require ever more increasingly expensive infrastructure to serve them. By both creating more distance between everything, and requiring more and more cost to cover those those distances, the productivity advantage is lost.

Essentially, driving improves productivity – up to a certain point. That point is when it gets to such a scale that it costs more and more to simply enable it to function at all. That's when driving demands so much space and infrastructure that it begins adding to the time and distance between transactions rather than shortening them.

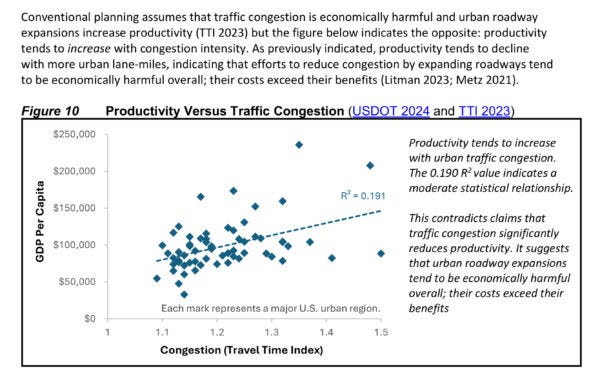

In other words, there is inevitably a point at which the costs of further expanding this new system become greater than the benefits. Indeed, that point seems to be well in the rear-view mirror now. In the United States, and presumably other economies with similar auto-dominant systems (like New Zealand), we are now well into overshoot:

To me, the chart above screams: saturation. The US has gotten as much as they ever will out of the driving/dispersal model. They're now firmly into good money after bad territory. Investments into expanding highways are now likely making the US poorer, rather than richer:

This is why, in driving-dominant cities, much more value is going to come from investing into all the alternatives to driving systems. This enables more people to opt out of the increasingly dysfunctional driving network more often, while still engaging in the economy. And, helpfully, the more people who are able to opt out, this more this helps keep that network more viable for longer, with a lower infrastructure cost for those who still drive.

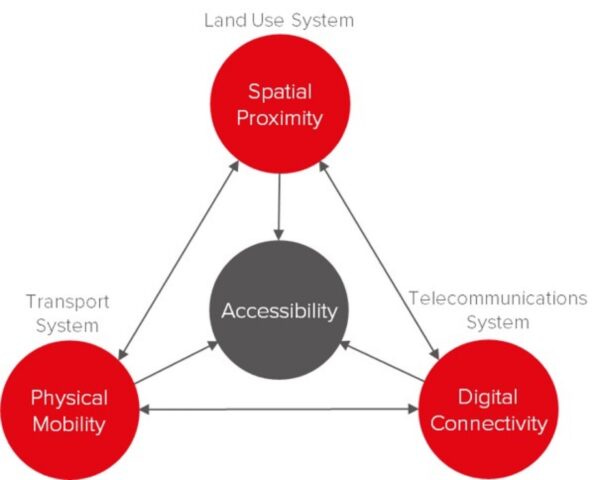

Every person on a bus, a train, a bike, or a ferry; everyone living closer together and more proximate to their work, study and play; and everyone connecting remotely as a substitute for commuting (when viable), is helping to increase our overall economic productivity.

This is why it is important to talk about access rather than just mobility, because not all better alternatives are transport investments. All three higher-productivity means of connection (alternative modes, more proximate urban form, and virtual connectivity) are more valuable now than a new additional motorway lane.

But they don't just include physically moving faster, as illustrated here in the Triple Access Planning model.

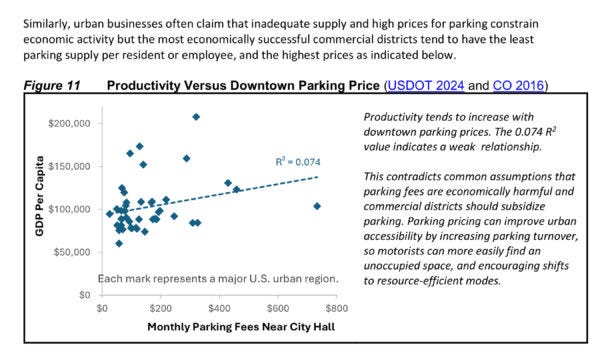

More evidence from the VTPI paper:

We can therefore conclude that over the last 20 years, investments that have helped shift Auckland's urban form inwards and upwards have supported higher productivity in the economy. For example:

the Northern Busway

Rail electrification and expansion

the New Bus Network

City Rail Link

the urban cycleways network

And also:

broadband

planning liberalisation, e.g. the Unitary Plan

city-centre place quality upgrades (enabling more urban living).

At the same time, these have been counteracted by almost continuous sprawl and extension of urban and exurban motorways. These are likely mixed: negative, in that they enable sprawl, but positive so long as they decrease inter-regional travel times.

Todd Litman calls this a paradox; I'm not sure it is, or least is only in the context of the continual claims that building more roads of any kind, anywhere, is always valuable. This study suggests we should take a much more sceptical view of those lazy assumptions.

This post, like all our work, is brought to you by the Greater Auckland crew and made possible by generous donations from our readers and fans. If you’d like to support our work, you can join our circle of supporters here, or support us on Substack!